GRIEF IN THE TIME OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Patty Somlo

Creative Nonfiction

If you are anything like me, Mount Carmel might be a place you’ve always dreamed of going. In early October, the fields are green. Sparkling streams catch the light and reflect wispy clouds, as water cuts through the grass in curves that make an artist’s heart quicken. The bed and breakfast where we lucked into a last-minute reservation sits back from the two-lane highway. In a fenced corral, four handsome horses swish their tails against the flies. Two of the horses are miniatures, adorably pudgy, with huge eyes. One of the miniatures is a blond.

Mount Carmel consists of a gas station, a restaurant or two, several scattered farms and little else. It sits outside the eastern entrance to Zion National Park. A second national park, Bryce Canyon, lies a short distance north. Several awe-inspiring national monuments can be found south, including the Vermillion Cliffs and Grand Staircase-Escalante. If you keep driving, you’ll eventually reach the North Rim of the Grand Canyon.

My husband Richad and I came here by car, from our home in Wine Country, an hour’s drive north of San Francisco. We took our time, spending one night in Tehachapi, California, and a second in St. George, Utah. Outside St. George, we got our first glimpse of the red rock that makes Southern Utah such a tourist draw, in Snow Canyon State Park.

After spending the night at a Best Western in Tehachapi, we enjoyed a free breakfast in a large dull room, where a big-screen TV was broadcasting the news. There, we came face to face with one of the horrifying realties of modern American life. A gunman in a hotel room on the Las Vegas Strip had mowed down an undetermined number of outdoor concertgoers the previous night. Later, the death toll of the deadliest mass shooting in the United States would be confirmed at fifty-eight.

Passing the Strip on the freeway some hours after, we couldn’t miss the marquee sign at the Mirage Hotel. Instead of advertising an upcoming show, the Mirage was pleading for donations of blood.

Being in Mount Carmel makes you feel that you’ve stepped into an idyllic past. There’s the landscape, of course, lacking tall buildings or even the sameness of suburbs, with their drab strip malls. You also can’t help noticing the people who are dressed as if it were a much earlier time. We see countless women and girls, wearing long, unflattering cotton dresses, faded from too many washings, with an abundance of thick hair, folded over into a strange hump atop their heads. One of these women helps serve the scrumptious, too-much-food breakfast we share each morning with our fellow guests, nice, interesting people from all over the country and the world. Another of these women takes our order, at the pizza place down the road. When I return home, I will learn that the area around Mount Carmel is home to a fundamentalist Mormon sect.

During this idyllic stay, we’ve barely connected to the rest of the world. We can’t get Wi-Fi in our otherwise comfortable cabin. Neither do we have a TV.

But every night after returning to the B&B, we hurry into what Richard and I have started calling the Wi-Fi Lounge. We rush because the room closes at nine. The dark snug space down the short hall from the breakfast room in the main house resembles an old tavern. Crimson Naugahyde booths line one wall. We often run into a young Dutch couple each evening, as the cute blond wife is posting descriptions on Facebook of that day’s sights.

It’s in the Wi-Fi room during one of our final evenings at the B&B that we learn of the fires. Richard’s and my Yahoo accounts are crowded with emails from members of our Unitarian Universalist congregation back home. Some senders are offering places to stay. Others are frantically searching for information about missing friends.

“There’s been a fire,” I tell Richard. He nods, a sign he already knows.

My throat feels scratchy and dry, a common reaction when I get scared. My stomach aches.

Initially, Richard and I are confused about what has happened in and around our hometown. As I read more, eventually getting to the site for the local paper, The Press Democrat, what everyone in our town, Santa Rosa, and county, Sonoma, refers to as the PD, I begin to put the pieces together. In the middle of the night, strong winds barreled over the Mayacamas Mountains that separate Santa Rosa and Sonoma County from the town of Calistoga and its county, Napa. Sparks from a fire that started on Calistoga’s Tubbs Lane blew over the mountains into the Santa Rosa hillside neighborhood of Fountaingrove. From there, fire raced down the hill, crossed the four-lane freeway, and torched the modest homes of another neighborhood, Coffey Park, before heading further east, destroying numerous manufactured homes in a senior park known as The Orchard.

While the Tubbs Fire would turn out to be the most deadly and destructive, it wouldn’t be the only blaze that moved in and through Sonoma County and our town that night. A second fire travelled through the Sonoma Valley east of town, a stunning area filled with vineyards and world-class wineries. That fire edged into the state park not far from our house.

The following evening while Richard and I are waiting for several dishes we’ve ordered in a Chinese restaurant in Kanab, I check the PD for the latest updates. Since the start of this disaster, the PD has been the main source for evacuation orders and warnings, and about containment of the fires. My eyes move down the list of evacuation warnings moments after Richard leaves for the restroom. That ache in my belly returns. Among the neighborhoods I’ve seen on the list, I’ve spotted ours.

Of course, it’s stupid and counterintuitive to shorten our vacation a few days early and return home after being warned to be ready to evacuate our house. But this is the first major wildfire to escape the non-urban core and run through our city, destroying everything in its path. Later, we will understand how such fires operate, in a time of long-lasting droughts and climate change. On this night, we decide to head home. How can we possibly enjoy the rest of our vacation when our home might be in danger and people we know have already lost theirs?

The air is chilly the next morning, as we load the car in the dark. Though the days have been warm, it’s early October. Brisk nights are a reminder that the short dark days of winter aren’t far. The sky lightens as I edge close to the fence and bid goodbye to the shy blond miniature horse I’ve grown during my brief stay here to love.

No one is manning the eastern gate to Zion this early, so we speed right through. Sunlight paints the red, orange and green rock that rises along the road into a perfectly clear cobalt sky. Even sitting in the car, passing the landscape calms me. Beauty still exists in the world, assuring me that everything will be all right.

Since we’ve abandoned the B&B hours before the breakfast service, we scout out a restaurant in St. George and pull into the lot. While we wait for our food, Richard calls a neighbor to see what he can learn.

“Oh, that’s good,” I hear Richard say, and feel a bit hopeful.

Richard gets off the phone and tells me everything around our house is fine. Later, we learn that the PD made a mistake, including an evacuation warning for our neighborhood.

I recall our idyllic stay in Mount Carmel, bookended by twin disasters, after reading the news that a distant fire has, without warning, wiped out a much-beloved town. Like people living in the hardest hit areas of my city and surrounding rural areas during the awful October night that brought high winds and fire to their lives, residents of Lahaina, Maui have endured incomprehensible horror. Learning of the widespread loss and mourning the deaths and destruction of people’s lives in a place I have visited many times, I realize there are collective griefs we suffer, as Americans and residents of this planet. They come one after the next, as a result of climate change and the irresponsible ways we persist in living our lives.

For me, grief stands out because I dwell in that state now and have for months, since the death of my husband Richard. It’s also why the memory of our time in Utah, hiking on trails amidst the variegated-colored rock, has come up. Though we didn’t know at the time, that visit would be the last major trip Richard and I would enjoy before stage four cancer entered our life.

The disastrous fire in Maui, scorching heat this summer in much of the United States, and years of drought followed by a season of endless, drenching downpours causing downed trees and massive flooding here in Northern California, are just some of the symptoms of our sick, and perhaps dying, country. During the four and a half years in which Richard was treated for stage four cancer, and the months I have been grieving following his death, our climate has also moved into its own stage four.

Day after day, reading about the unrelenting heat blasting large swathes of the U.S. and the Maui fire, exacerbated by climate change-fueled drought, I experience bursts of sorrow, similar to those that hit when I’m missing my husband. This other climate grief comes from a deep sadness that we are rapidly losing what, for lack of a better term, I can only call normal life.

Both losing my spouse and watching the climate move so rapidly into near life-threatening territory bring a frightening unpredictability to life. Death and disasters do that, making you feel that the ground is shifting below your feet. You fear falling any moment into a deep abyss.

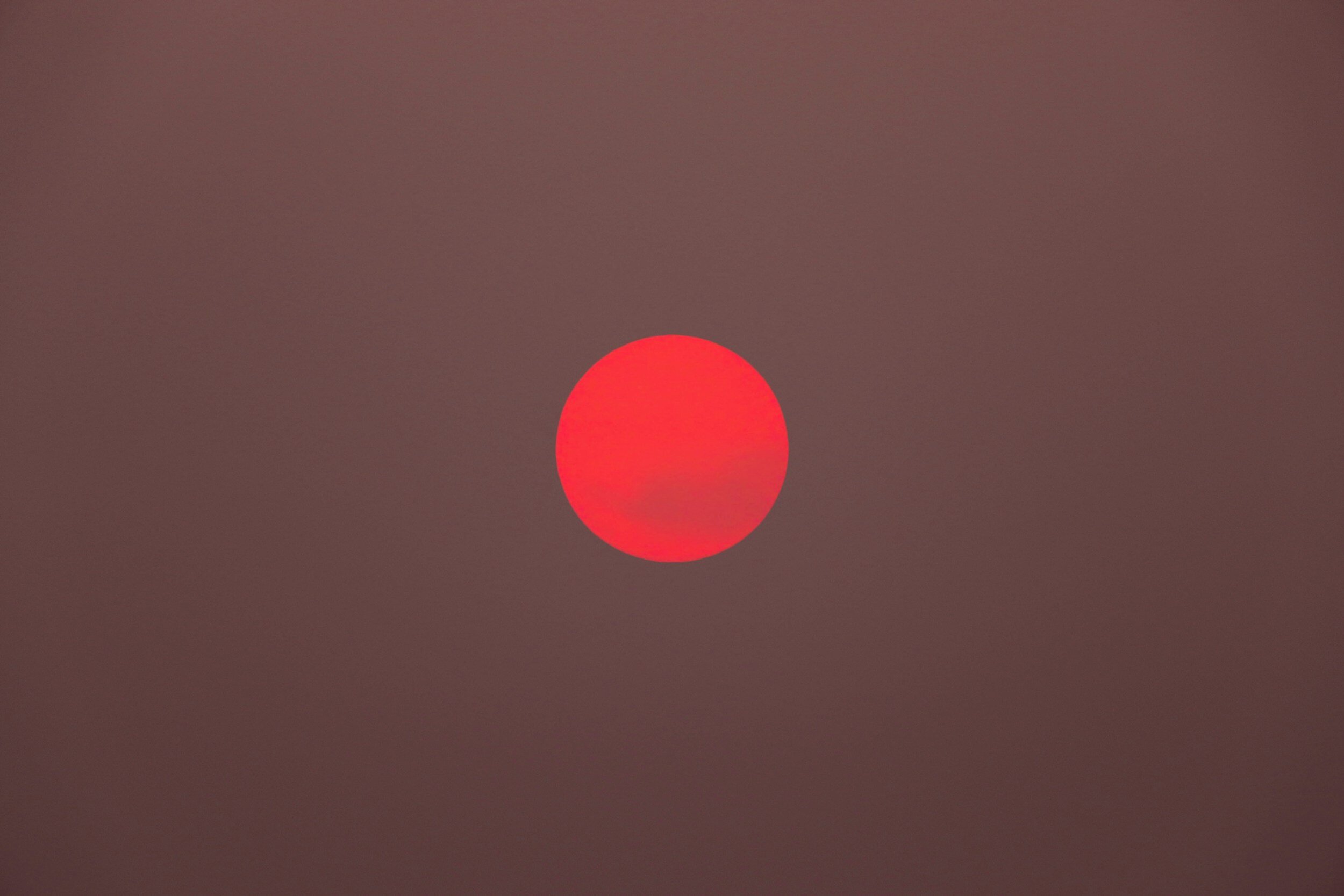

Just as my husband’s death was a long time coming, with the cancer and chemo robbing him of energy, abilities and strength, the symptoms of our warming climate have been around for quite a while. Richard and I shared a love of nature and left the city as often as possible, to hike mountain trails, kayak in rivers and lakes, or snorkel in the clear waters off the coasts of Maui and Kauai. Even years ago, there were times when we travelled to a new or favorite place and smoke from a nearby wildfire darkened the sky. One summer, we rented a cabin in Sechelt, feet from the inlet of the same name, on British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast, a short ferry ride from Vancouver. An uncontained wildfire further north drenched the sunsets every evening in a fierce orange glow. More than once when we visited Yosemite National Park, wildfire smoke obscured the view of the famous granite slabs that line the Valley. Even though smoke didn’t cloud the sky every day we were in Glacier National Park, we couldn’t ignore the sprawling tent city on the outskirts, where firefighters from all over the world ate and slept, when they weren’t out battling the nearby blaze. During a stay in Strawberry, California, overlooking the Stanislaus River, we listened to the grating whine of electric saws and passed workers alongside the road, as they felled trees, deadened by persistent drought.

Anyone paying the slightest attention knows. The cancer spreading through our planet for decades has rapidly speeded up. In Northern California, we’ve learned what can happen when something as simple as the wind shifts. Instead of the cool breeze blowing in from the ocean, which normally brings evening and morning fog, hot wind barrels over the mountains from the east, insuring that one spark will explode into a massive wildfire threatening towns. The experience with fire has made us more prepared, but climate change keeps us surprised.

In the time since my husband’s passing, I have learned the ins and outs of grief. At any moment, it’s liable to hit. Reminders of my husband wait everywhere. A trip to the grocery store, seeing foods Richard loved or realizing how little I buy now with only myself to feed, brings tears to my eyes.

What about the destruction of beloved places? How does it feel to hike a favorite trail after a fire, passing charred black stumps?

My earliest memories are set on the Hawaiian Island of Oahu, where I lived with my parents and two sisters for three idyllic years. In the back yard of our first home, we had a banana tree, on which tiny fat fruit grew, curled like a baby’s fingers. I studied the hula and performed on the beach, before luaus and outrigger canoe races. But amidst all that I remember, what stands out is riding the tremendous waves on the often-cloudy Windward Coast.

For hours each day, I would paddle out to the smooth water place, ahead of which waves started to swell. Once I’d mastered reading the waves, how they gradually built, then fell forward, I came to trust the ocean. I would wait until I saw the swell begin, and then paddle ahead, to be in the right spot where the ocean, like my very own private vessel, would lift me up and ferry me to shore. Times I misjudged, and the wave pulled me under and tossed my body around, I still managed to paddle up to the surface unharmed. Decades later whenever I step into the ocean, or stand on a beach looking toward the horizon, I feel a sense of peace and familiarity, as if I’ve finally returned home.

I left Hawaii, sailing out of Honolulu Harbor on the S.S. Matsonia, the summer before I entered the fourth grade. Before leaving, my mother, sisters and I stood next to the railing and tossed our orchid and plumeria leis into the water. Though I strained to see the fate of my lei as the boat moved out to the open ocean, I didn’t learn if my lei made its way to shore, a sign I would one day return. But I did return, over three decades after I’d left, not to Oahu but to neighboring Maui.

A few months after that visit, I met the man who would become my husband, on a blind date. Though we’d only agreed to meet for lunch, at a restaurant overlooking San Francisco Bay, Richard and I ended up spending the afternoon and evening until midnight together. On that initial date, we became aware of a shared love of nature. Soon, we started leaving the city every chance we got.

Within six months of meeting, we were hiking trails on the North Shore and in Kokee State Park on the Island of Kauai. Months after that, we were snorkeling in the Āhihi-Kīna‘u Natural Area Reserve on Maui.

When I think about that Maui stay, my grief over Richard’s death and the disaster in Lahaina come together. Included in the near total destruction of the homes, businesses and historic sites in Lahaina Town from the massive fire were the docks where tourists could board whale-watching boats, to sail out and witness the awesome sight of humpback mothers and their calves breaching. February, the month we were in Maui, is the best time to see the humpbacks, as they feed and rest on their long journey north from Baja, Mexico.

Richard had long had a phobia about boats, resulting from a frightening experience during childhood. He assumed, without proof, that sailing on rocky water would bring on a bout of sea sickness. Thankfully, the promise of seeing humpback whales and capturing them with his medium format camera bolstered his courage enough to agree to go on a whale-watching cruise with me.

An hour before sunset, we boarded the boat from one of the now-destroyed Lahaina docks. Richard took a seat on a crowded bench, where he’d be able to see, but also keep his camera dry, and, hopefully, feel safe. I stood near the front of the boat, not caring if I got wet.

It didn’t take long for the captain of our boat to spot a mother and calf. He stopped the vessel at the required minimum safe distance. The huge mother humpback soared into the air, as if on wings. Moments later, her calf followed.

I looked back at Richard. The viewfinder of his camera was pressed to his right eye, the fear he’d felt before we boarded nowhere to be found.

As much as I worried about Richard dying the entire four and a half years he received chemotherapy, radiation, and finally immunotherapy, treatments aimed at prolonging his life, I somehow kept the acceptance of his coming death at bay. Since that awful event, I’ve learned. Denial of illness, and ultimately death, keeps us from being fully alive.

Part of this attitude I have found in my own life, what I can only describe as an absence of gratefulness. To acknowledge the likelihood I will die, forces me to be thankful for so much, and to live each moment as if it were my last.

The same attitude is necessary in the face of our world’s increasing disability. If a wildfire races into town and I manage to escape with nothing, I will now be exceedingly grateful for still having my life.

As I write this, a cool breeze from the coast has pushed out smoke that yesterday darkened the sky and choked the air, from a wildfire hundreds of miles to the north. I feel grateful for what I took for granted only a few days before – being able to go for a walk, not worried about breathing in toxic smoke.

Long before Richard’s death, the wonderful life we shared began to change, as the cancer and chemo took a toll, draining my otherwise active husband of energy. Our life, which once centered around time enjoying beautiful places outdoors, now focused almost exclusively on keeping Richard alive.

Like cancer, climate change has altered my life and those of many other people. In my small Wine Country city, nearly everyone has been permanently scarred by the fires that hit in recent years. On the surface, those who lost homes or businesses in the devastating 2017 fires have recovered, either deciding not to rebuild and moving elsewhere or having constructed a replacement home. The trauma of having to escape in the middle of the night as the wind-driven sparks threatened their lives, though, doesn’t ever completely disappear.

The loss of housing in already overpriced locales, such as my town and the Island of Maui, makes it impossible for some long-time residents to stay. Even if affordability isn’t an issue, people move on, because they don’t want to live with the fear that one day strong dry winds will bring flames to their home, taking everything they own away.

For years before Richard’s death, we rented a cabin in late summer or early fall in a wondrous place we’d grown to love, the Lakes Basin Recreation Area. During two summer visits, we stayed in a rustic former miner’s cabin on the banks of the Yuba River. The small square structure was set in the trees off winding, scenic Highway 49, a few miles north of the historic town of Downieville. After leaving the car parked in a dirt clearing, Richard and I piled our luggage and bags of food into an old metal miner’s cart and dragged it across a swinging cable bridge that spanned the river. The cabin sat on the other side.

The Lakes Basin Recreation Area, including the small towns of Downieville, Sierra City and Graeagle, doesn’t attract big crowds, like Lake Tahoe, an hour’s drive north, does. Once kids go back to school in August, and especially by September, the lakes and trails on weekdays are practically empty.

The year after Richard started chemotherapy, the Covid-19 pandemic kept us from our usual visit. Once life opened up the following year, we were looking forward to going. I made a reservation for a vacation rental to coincide with our anniversary in late August. But this time, climate change, not Covid or cancer, was the culprit.

The State of California had been in a drought for five years, and in many counties had reached the most severe level, Exceptional Drought. Wildfires were burning throughout the state, having started earlier than what had once been considered fire season in the fall. It was now accepted that fire season in California lasted all year long.

For weeks before our scheduled stay, I anxiously consulted the daily Cal Fire reports on the status of a blaze with little containment, not far from where we planned to go. As late August grew closer, I was relieved that fire hadn’t spread to our favorite town. Yet, smoke was still choking the air.

Unless we wanted to sit in our kayak on Packer Lake breathing in toxic air, which we didn’t, we needed to cancel. When I called the vacation rental company, the owner suggested we postpone for another month. She found us a nice rental at a later date. I kept reading the Cal Fire reports.

The fire continued to spread, as dry weather with its low humidity and strong winds pushed the flames further. As the time grew near, I accepted the fact that we wouldn’t be able to go and went ahead and cancelled. Given my husband’s condition, this meant we would never go to the Lakes Basin Recreation Area together again.

The first summer without my husband, I grieved for the planet that is my home. Since childhood, spending time in nature has always brought me joy, and after Richad’s death, I had hoped it would again. Not only had I been left to travel alone without my favorite companion, but I was also forced to accept that climate change would make it even harder.

Every summer, wildfires are forcing residents and tourists to evacuate beautiful places throughout Europe, and this year, across Canada. In the U.S. and Europe, heat domes have settled over cities, towns, and beach resorts, making it too hot to spend time outdoors. It’s not unrealistic to wonder if in the not-too-distant future these places we all love will become too hot, dry, or dangerous to visit or live.

As a child growing up in a military family, I became all too familiar with loss. We moved on average once a year, or every other year, packing up and leaving a home, friends and favorite spots, and heading somewhere we’d never been before. This life might have been easier if each time, my parents helped us grieve the loss. I don’t recall us ever talking about the sadness of leaving. We were simply expected to move on.

I didn’t realize until much later in life, but in every town, or around each military base where we lived, I tried to find some spot outdoors that I loved. In Hawaii, of course, there was the ocean. After Oahu, we moved to a small New Jersey town, where I loved to walk. At least once a week, I strolled beneath massive ancient trees and past stately eighteenth-century homes on Main Street, to and from the library. I also hiked up the Mount, for which the town, Mount Holly, was named, collecting red and yellow leaves in the fall and pressing them between waxed paper in my school textbooks.

Later, living on a military base in Germany, I rode my bike on paths through the woods to small towns, and occasionally travelled to the snow-covered mountains to ski. Everywhere we lived, nature saved me.

In the early evening on the day Richard died, I went for a walk. The leaves had turned yellow and red and were glowing, touched by golden light. The deep sorrow I felt suddenly lifted, eased by the warm, caressing breeze and the luminescent color around me. As I had told Richard many times in his last weeks, I was going to be sad and miss him forever. But in this moment, I held onto hope I would find solace and comfort, in this wondrous planet, which I would work to save the rest of my life.

Patty Somlo’s most recent book, Hairway to Heaven Stories, was published by Cherry Castle Publishing, a Black-owned press committed to literary activism. Hairway was a Finalist in the American Fiction Awards and Best Book Awards. Two of Somlo’s previous books, The First to Disappear (Spuyten Duyvil) and Even When Trapped Behind Clouds: A Memoir of Quiet Grace (WiDo Publishing), were Finalists in several book contests. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Gravel, Sheepshead Review, Under the Sun, the Los Angeles Review, The Nassau Review, and over 30 anthologies. She received Honorable Mention for Fiction in the Women’s National Book Association Contest, was a Finalist in the Parks and Points Essay Contest and in the J.F. Powers Short Fiction Contest, had an essay selected as Notable for Best American Essays, and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net multiple times.