Damming the SentimentaL

Kate Beck

This is where a new dam might go. The blue is what currently exists of the Bow River, the natural and unnatural twists and pools. The red areas are the cities, Calgary and its smaller neighbors. The Yellow is what the Alberta government has claimed is the Stoney Nakoda Nation’s lands, but of course, the government’s land acknowledgement says that it’s all theirs, and the Blackfoot’s and the Metis’ and Tsuut’ina’s. All of these colors are places that exist. The little black stitches are ideas, ideas of where the Alberta government may flood, maybe not forever, but for an incredibly long time.

1. This is what’s happening.

The Bow River is a reason Calgary exists, along with Northern oil. As the oil has dried and warmed the world, causing the city’s economy to turn, fall, sputter, then start, the Bow River’s main glacial source has been receding. Floods are becoming a consistent part of Southern Alberta and Calgary’s seasonal life. I didn’t know there was flooding this year in Calgary, the city that raised me. Colleen, my friend I’d grown up with and who’d decided to stay when I decided to leave, told me Calgary was prepared. They put sandbags along the major roads. Neighborhood streets were still sunken with water. She didn’t say anything about how everything outside of the city fared.

The provincial government is proposing to build a dam that promises to mitigate both droughts and seasonal floods by permanently flooding parts of the Stoney Nakoda Nation’s reserve or rural community, maybe. After I first heard about the new dam, I sat at my computer in California, and I watched drone footage of the treed hills and valleys it might permanently drown. The drone meticulously avoided signs of humans, attempting to show me that it’d all be fine. Some trees would be drowned in this process and nothing else. This future dam haunted me. I included this on my list of sorrows along with things like my sick dad, my sore neck, smoking skies. When I’d review these sorrows, I’d repeat “and they’re building a new dam in Alberta” in my mind, then catch my use of the term “Alberta” instead of “home.”

Last night I dreamt of a map showing a tributary of the Bow River providing water to my street in California. I didn’t remember the dream until drinking my new city’s tap water and remembering how much I dislike the taste.

2. I’ve been gone for a long time.

I left Calgary 12 years ago. I counted the years since I’d left when texting my friend Josh—one of the people who asks me when I think I’ll come back—and the number surprised me. I’ve lived in California awhile and I used to hate how much more known this place is than my home. Now, the hate has worn to soft annoyance, and I draw pictures of the Bow River in May while driving through Tahoe’s forests in August. I like to tell myself that I wouldn’t care for Calgary like I do if I hadn’t left. But long-distance relationships with places, like with people, are difficult.

These words and images are my attempt to understand the history of the river and its humans, the political and emotional decisions being made about the dam, and the future of my home and the lands and waters it relies on. This attempt is made up of real things and dreams. It’s a conversation between me and people who I know and do not know. It is confusing and fragmented because that’s what understanding a place is, especially from afar.

Fish Creek’s Water Treatment Facility. So many of our problems feel new and big, but they’re the same problems we’ve faced before.

3. Capitalism requires predictability.[1]

I read books to understand the things on my list of sorrows, hoping that knowing more will massage a sorrow into achy acceptance. The dam is a thing I read about and can’t let go of.

I learned that our attempts to control rivers are not new. The Harappan people from South Asia lived along the Ghaggar-Hakra River valleys in today’s Pakistan and northwestern India. They lived and worked on one million square kilometers, bigger than Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations combined. They found ways to control the river’s water through plumbing, toilets, baths, aqueducts, and sewers. The Harappan aren’t well studied in comparison to other civilizations; it’s unclear why this civilization ended. One thought is the river dried up because monsoons weakened, making the area too dry to grow crops and fill the plumbing.[2]

Attempts to control rivers happen over and over again. Mesopotamia means “land between the rivers”. The rivers along the edges of this growing place were unpredictable, and they built infrastructure to control and increase its predictability. This infrastructure was one of the ways Mesopotamia became a city, what some people consider the first city. When the rivers shifted, no longer serving the city, the city dried up too.[3] We have been so good at pretending we have control.

This image looks unfinished, but it’s actually missing. It’s missing the ice that has receded from the Bow Glacier from 1900 to 2010. It’s showing how little the beings that rely on the river have left, how much melted ice they need to catch before it runs elsewhere.

4. This is the Bow River.

The Bow River’s banks are where people wintered together, sheltering from the wind. In the springs, they would relocate up to higher ridges, taking advantage of the warming sun, moving further from the river’s flooding edges and faster currents, maybe. For so many indigenous groups, this river valley was a set of travel corridors and food and wide-open views. It was, and still is, a place to plan and rest and meet others.[4] Do you see the difference here? These weren't attempts for control, this was flexibility for the river’s ebbs and flows and changes in direction.

Then, others came. On some fur trading maps, the Bow River was labeled the “bad river”[5] because it didn’t have what these Europeans wanted. But then the things we wanted changed and the river became okay, even important. The river changed from a place where small groups of men couldn’t find furs to a place that settler families wanted to live beside and travel on and eat from too. We wanted to do more than stay on the rivers’ edges for the winters, we wanted permanence.[6]

Rivers aren’t permanent. They’re meant to fluctuate in width and depth from season to season and turn in different directions from one year to the next. They have what we need to survive, but they don’t have permanence. So, like the Ghaggar-Hakra and Mesopotamia’s rivers, we started to find ways to control the Bow River.

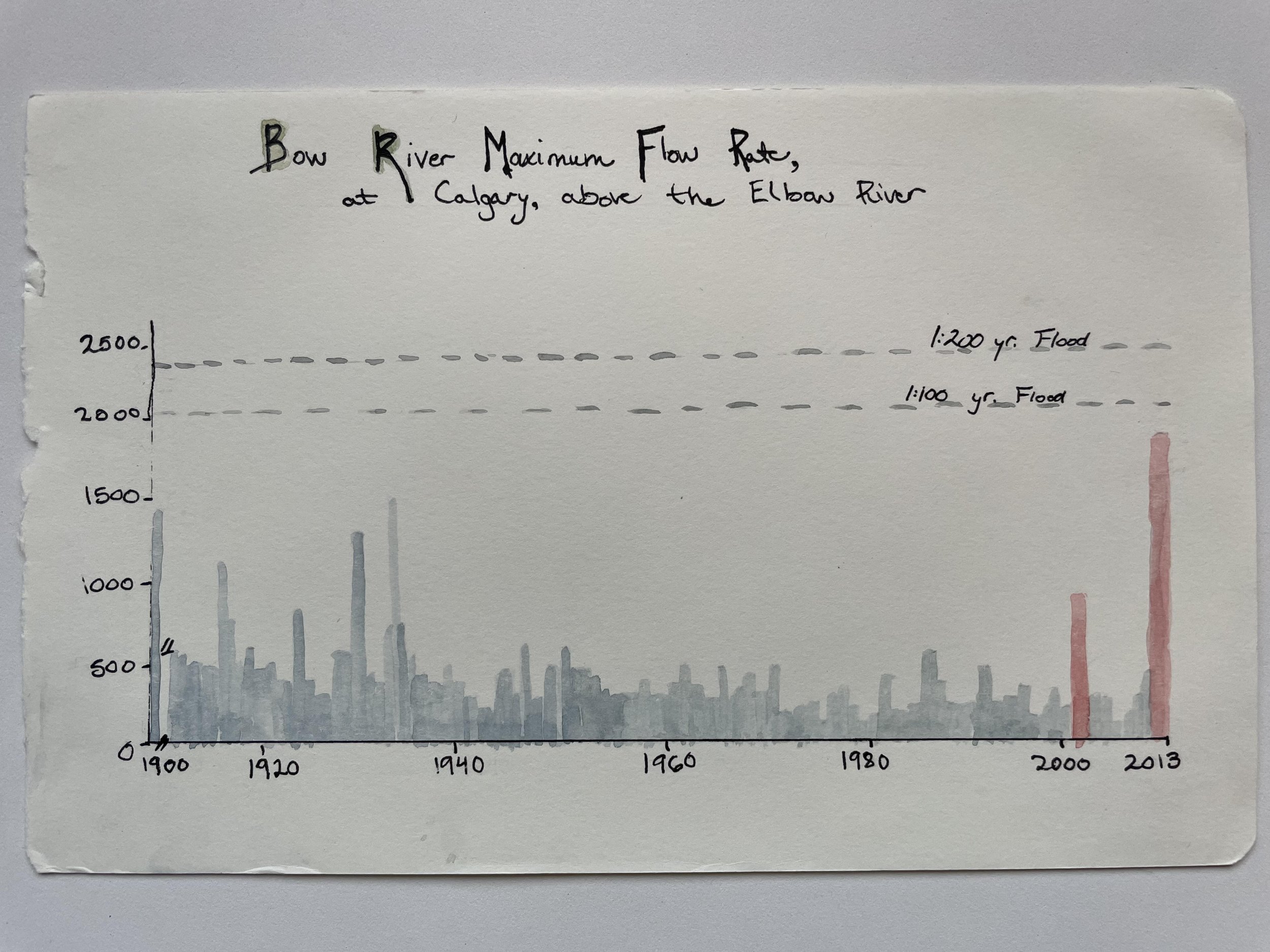

Calgary’s existing dams, built in the 1940s until the 1960s, limited the variability of the Bow river’s flow rate[7] and prevented seasonal floods. The dams did this until the storms started getting bigger causing flooding marked in red. We're told that the storms are going to keep going this way.[8]

5. Floods mean so many things.

In my memory, everything was fine until recently. The Bow River would expand with spring rains and slowly settle back to its shallower depths over the summer, rarely pushing past its edges. Wetlands eased the seasonal floods, holding extra water deep in their marshy bellies.

But then there was the 2005 flood, and we were told it wouldn’t happen again. Then there was the 2013 flood, and we were told that the Alberta government now needed to make sure it would never happen again. One time, Donna, a friend of my mum’s who has lived along the river for the last 10 years or so, told me the exact flow rates that will flood her basement each spring, one number for when the basement will be flooded by rising groundwater, another for when it will be flooded by rising surface water.

The city has been pushing its own edges, paving over those wetlands that once held the spring water. So, the provincial government has been coming up with other ways to deal with the excess. The new dam is supposed to bring the river back to its banks even with bigger storms and increased glacial melting.

An advisory committee guiding the provincial government on building the new dam proposed to limit maximum flow rate to 400 cms to stop spring flooding. Then they realized that this flow rate would require a lot more work and there could be “detrimental effects on the natural functions of the river.”[9] So the committee set the seasonal flood mitigation flow rate to either 1200 or 800 cms. 1200 cms would require one major piece of infrastructure, like a new dam, or an expansion of an existing dam, and 800 cms would require two of these dams or expansions.[10] Donna needs two pieces of infrastructure to prevent her basement from being drowned in the spring.

The Province’s advisory committee doesn’t mention specifics of the “detrimental effects on the natural functions of the river,” which, it turns out, will occur when any dam is built. It doesn’t mention that seasonal floods are a way of removing debris and moving nutrient-rich river sediment to different parts of the river and its floodplains. Floods fertilize. Floods provide species, particularly native species like the aspens, like the snowberries, saskatoons, prickly roses growing underneath, with what they need to continue to live.

The Ghost Dam, one of the seven dams currently on the Bow River, is a dreamt-of-then-built castle. It was made to collect hydro-electric power, forcing the river into a lake with perfectly symmetrical waterfalls, but it’s still a castle on a river.

6. “The depiction of nature as apolitical is itself a political act.”[12]

I’m told that the provincial government is probably going to extend one of the existing dams, the Ghost Dam, which will gulp up part of a small town outside of Calgary. When this dam was first built, Calgary’s worries were about energy for an increasingly populated, industrializing city rather than the river floods that happened from time to time. The Ghost Dam was an energy company’s attempt to meet the booming 1920s’ increasing desire for electricity. They went big, building a dam that looked like a castle and that would almost double the company’s total energy production. And then, of course, the Great Depression came, and the energy company was wrong about its increase-in-energy-consumption imagining.[13] The company was left stumbling, grabbing for ways to pay for this castle. And still, the valleys at the head of this dam, the confluence of the Ghost and Bow rivers, were put under water, turned into a lake. And now, this castle might be rebuilt, gulping up more of the valley. This is when I realize how deeply this province has dug itself into the idea of permanence, and then, of course, I start seeing it everywhere.

I often think about a map I once saw of what California’s water might look like without human intervention. It showed the missing lakes and streams if dams, reservoirs, and river narrowings were to disappear. It names the maybe old but now new curves and pools things like “Honey River” and “Surprise Valley Lakes”.[14] I loved it, and it all felt like a joke, the map’s dreamy premise, the silly names.

Creating the potential locations for Calgary’s new dam is also an act of water imagining. But these imaginary dots and lines that add human intervention rather than remove it feel more legitimate than the Honey Rivers. Some imaginings are taken so much more seriously than others.[15]

The grasses and big prairie skies are things I used to know too well, but now I paint them from a collection of poorly organized memories.

7. I want to know what it would be like to have not left.

In California, I look through books to find authors’ references to a younger, more predictable Bow River. I want to find a deep understanding of humans’ relationship to this river, humans who haven’t left. I don’t find what I’m looking for, and I get frustrated by the lack of references to this river by all these authors who claim Calgary as their home. Instead, I find a poem that I like and don’t understand. The river fed this poet that I don’t understand, and I realized that this is often what living with water is. Water isn’t always about water. This poet does reference magpies, and I’m comforted thinking about the water that once fed both of us and our appreciation of suburban birds.

I do read narratives of people trying to control other rivers,[16] and I listen to people’s stories of trying to convince the provincial government to do something about the Bow River’s floods so they can stay in their homes. These are stories of labor, fear, communities pulled apart, places we love breaking, uncertainty. And I read and think about what it could mean to live with the river’s changes rather than in constant attempts to control it. These are stories of an impermanence this city does not know, of picking up and moving quickly when the river changes, of allowing the river to move in whichever directions it needs to.

Books and reports tell me that dams are about human control and economic stability and the drone footage and maps show me what might be drowned, and then I see it all.

8. Swimming waters

I’m in Calgary and the water is warmer than it should be for late August. The glacier keeps melting and the river is too warm for its fish.

During these too-warm weeks, I go to the Ghost Dam, and it looks less menacing in person. People are swimming and sailing and barbequing on this lake that is also an underwater valley. I swim too, watching my dad walk alone along the shores. I go birdwatching with my brother, paying very close attention to things, moving slowly.

By now I know that human relationships with nature are based on so many things. Nature as a retreat, as recreation, is a fleeting feeling in humans’ history and has required a level of permanence and predictability that is unnatural to many environments. And here it is. On this river that we have pushed so hard to be stable, people are barbequing, kayaking, storing sailboats. And maybe this is what it’s like to live up close to this river. Maybe it’s like holding the high waters of the warmer spring, remembering the specific flow rates you need to watch for, hearing elected officials scared about the river’s height on the radio, picking the saskatoon berries, swimming in the calm spots on hot summer days, planning around the water shortages, watching the snow fall lighter and later than before. Maybe it’s melting the glaciers, making the river swell then dry, knowing that maybe this home will dry up too, and watching some banks permanently flood to allow for others to never be, then kayaking, picnicking.

Close up and moving slowly, it feels softer to see all of the things we’ve attempted to control, extract, preserve, and love.

9. Contradictions

I know that this has happened before. I’ve seen my city replace and cover and build over and do so much to attempt to exterminate the inconveniences of the river and the people who have lived on its edges before the city was here. This province is so good at digging its heels in. It fights for its permanence to the point where we all question whether it can continue to exist, and then it finds new ways to warp this place into itself. Here it goes again, I now tell myself. It just keeps fighting the river for control of itself.

Ever since I left, I’ve said that I’ll go back to Alberta soon. When I first moved to the U.S., I’m sure I pronounced my o’s more strongly. I wanted people to know where I was and was not from so badly. Recently, I’ve noticed that my permanence to Alberta has gotten shakier, though. I’ve been finding ways to say that I belong to Alberta, but it doesn’t belong to me, that my summers and winter holidays are Canadian, while my pay cheques and kettle are American. And I don’t say this, but I know we're all thinking it, twelve years is a long time to say I’m coming back soon.

A few months ago, I found someone in this part of the world who knows the Bow River. We talked about her first date with the first person she really liked being on the river’s edge, about my dog who waded in the river on the last night of her life. We talked about this river being unwell, and how hard it is to be away from something that’s sick, how I can’t seem to do anything to help the river from afar and I’m not sure what I could do from closer either. We tell one another that sometimes we need to accept that there’s nothing we can do, then mourn, and maybe that’s what I’m doing now. After this, I check the weather in Alberta and see that it’s still smoky.

[1] Tyler J. Kelley, Holding Back the River, 2022, https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Holding-Back-the-River/Tyler-J-Kelley/9781501187063.

[2] Lawrence C. Smith, Rivers of Power, 2020, 18, https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/laurence-c-smith-phd/rivers-of-power/9780316412001/.

[3] Smith, 16.

[4] “Archaeology and Calgary Parks” (City of Calgary, 2020), https://www.calgary.ca/content/dam/www/csps/parks/documents/history/archaeology-and-calgary-parks.pdf.

[5] Christopher Armstrong, Matthew Evenden, and H.V. Nelles, The River Returns (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009), 25, https://www.mqup.ca/river-returns--the-products-9780773535848.php.

[6] Armstrong, Evenden, and Nelles, 25–80.

[7] Flow rate is the amount of water that passes through an area in a given period of time. It’s measured in cubic meters per second (cms) in this table.

[8] Graph source: “Bow River Maximum Flow,” accessed August 8, 2023, https://www.calgary.ca/content/dam/www/uep/water/publishingimages/floodinfo/bow-river-max-flow-full-size.jpg.

[9] “Bow River Water Management Project : Advice to Government on Water Management in the Bow River Basin,” 12–13, accessed August 8, 2023, https://open.alberta.ca/publications/bow-river-water-management-project-advice-to-government-on-water-management-in-the-bow-river-basin.

[10] “Bow River Water Management Project : Advice to Government on Water Management in the Bow River Basin,” 12–13, accessed August 8, 2023, https://open.alberta.ca/publications/bow-river-water-management-project-advice-to-government-on-water-management-in-the-bow-river-basin.

[11] “Get to Know the Bow River,” 2014, https://calgaryrivervalleys.org/get-to-know-the-bow-river/.

[12] Rebecca Solnit, Orwell’s Roses, 2021. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/607057/orwells-roses-by-rebecca-solnit/.

[13] “Ghost Hydroelectric Dam,” accessed August 8, 2023, http://www.history.alberta.ca/energyheritage/energy/hydro-power/evolution-of-an-industry/ghost-hydroelectric-dam.aspx.

[14] Obi Kaufmann, The California Field Atlas, 104, accessed August 8, 2023, https://www.heydaybooks.com/catalog/the-california-field-atlas/.

[15] Krista Tippett and adrienne maree brown, “We Are in a Time of New Suns,” On Being, accessed August 8, 2023, https://onbeing.org/programs/adrienne-maree-brown-we-are-in-a-time-of-new-suns/.

[16] Kelley, Holding Back the River.

Kate Beck is an Environmental Policy Researcher and Regional Planner from Calgary, Alberta. She currently lives in Washington State but continues to call Alberta home.