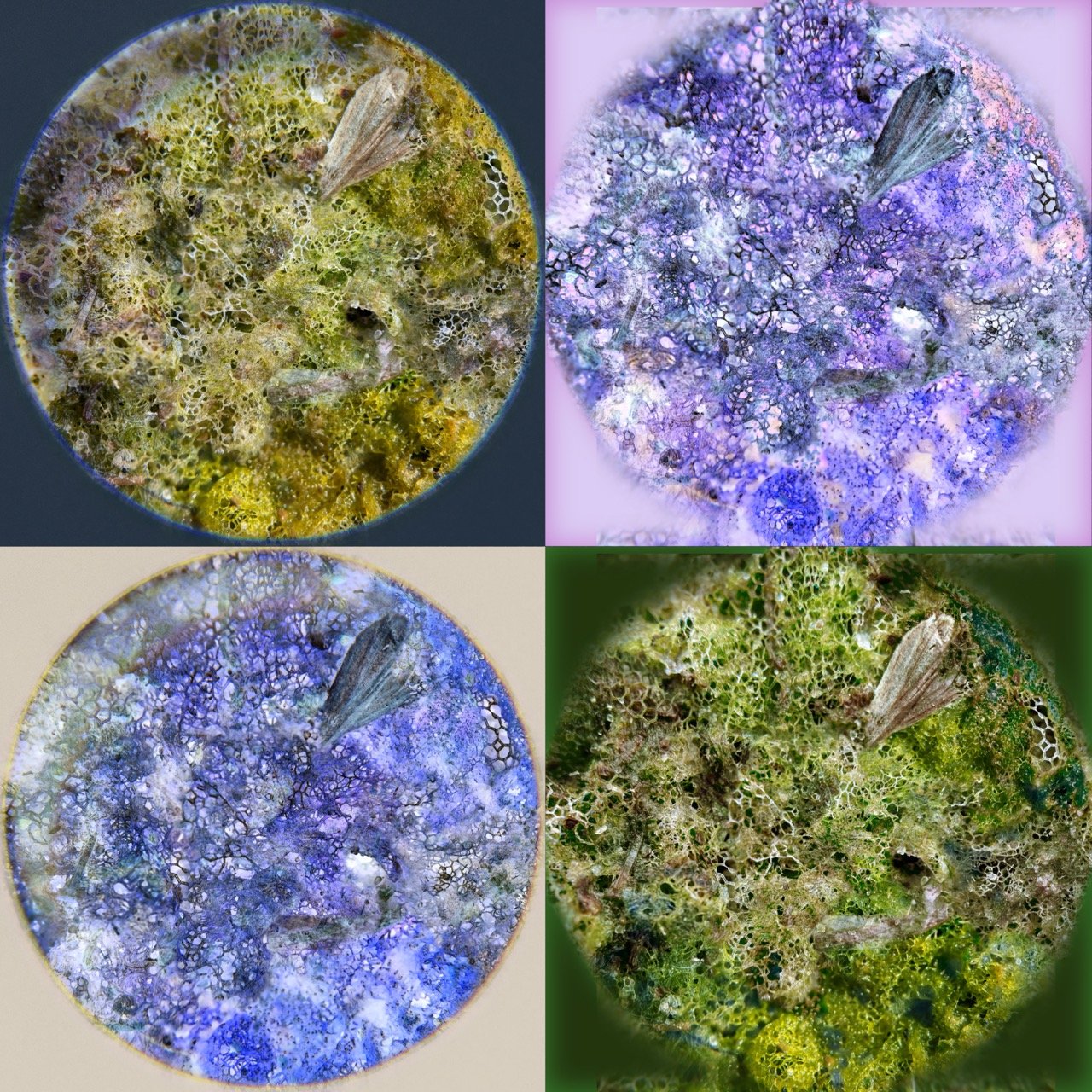

Detail from Marguerite Perret’s “32 Cloacina in Triplicate (Sphaerotilus)”

Climate’s Shipwreck Ballad

&

Transmutation Traces

A multimedia Exhibition

developed for the Plattsburgh State Art Museum

In 2023, longtime artistic collaborators Robin Lasser and Marguerite Perret were invited to SUNY Plattsburgh to develop an installation for the museum, inspired by Lake Champlain region’s rich environmental and social legacy. The exhibition that developed from that work opened in August 2024 and was on display through December. Thanks to the generosity of the Plattsburgh State Art Museum, Museum Director Tonya Cribb, and the artists themselves, we’re able to feature a selection of that work here, followed by an interview with the artists.

Climate’s Shipwreck Ballad

Robin Lasser

Shipwrecks may serve as an iconic metaphor for the current state of our earth. There are 300 wrecks below the waters of Lake Champlain, as well as 300 species of birds, flying above, utilizing the lake as habitat. Lake Champlain’s shipwreck burial ground serves as a timeline, a mariner archive of the industrial revolution to the present demarcating the era responsible for the climate crisis profoundly affecting our shared global commons, water. This exhibition features room-size immersive video projections, musical compositions, large-scale photographs and sculpture that are all inspired by faculty research occurring in the Lake Champlain Research Institute and The SUNY Plattsburgh Center for Earth & Environmental Sciences.

Artist Statement

These images are documentations of temporal, miniature installations I fabricate to be photographed. The ships, made from silicon molds of cast mini rowboats, steamboats, lifeboats, and cruise ships are filled with pigmented water, and then exposed to freezing temperatures.

Cameras capture the ice ships melting in time. As they melt, the tears of the shape-shifting craft form unique watersheds. The video demarcates the theater of dissolution, the still camera marks a moment in evolution.

Transmutation Traces

Marguerite Perret

A contemplation on the impact of anthropogenic activity on the interior watersheds, and the ecosystems and human communities that rely on them. There are three expansive and ongoing series represented in this exhibition.

The Plastic Romance Series, mixed media and photo-based archival prints, 2024, reflects on the tradition of romantic painting, especially that of the mid-19th through early 20th centuries. In this series, idealized nature gives way to the profusion of plastic sheeting, fibers, pellets, packaging and objects pictured dominating and subverting the landscape and waters. The setting for this series is City Park photographed one afternoon during a beach cleanup organized by Aude Lochet in September 2023.

Washed Up, porcelain and mixed media sculptures with photo-based archival prints and large-scale two-dimensional works, 2019—present. Human manufactured objects are cast, sculpted and combined with photo-based graphics to reference/imply a connection with aquatic ecologies. But while these appear to have organic origins, all were found in the consumer ecosystem, and the few ‘naturally’ sourced elements are either introduced species or plants purchased at a local home improvement store and consequently still part of human commerce.

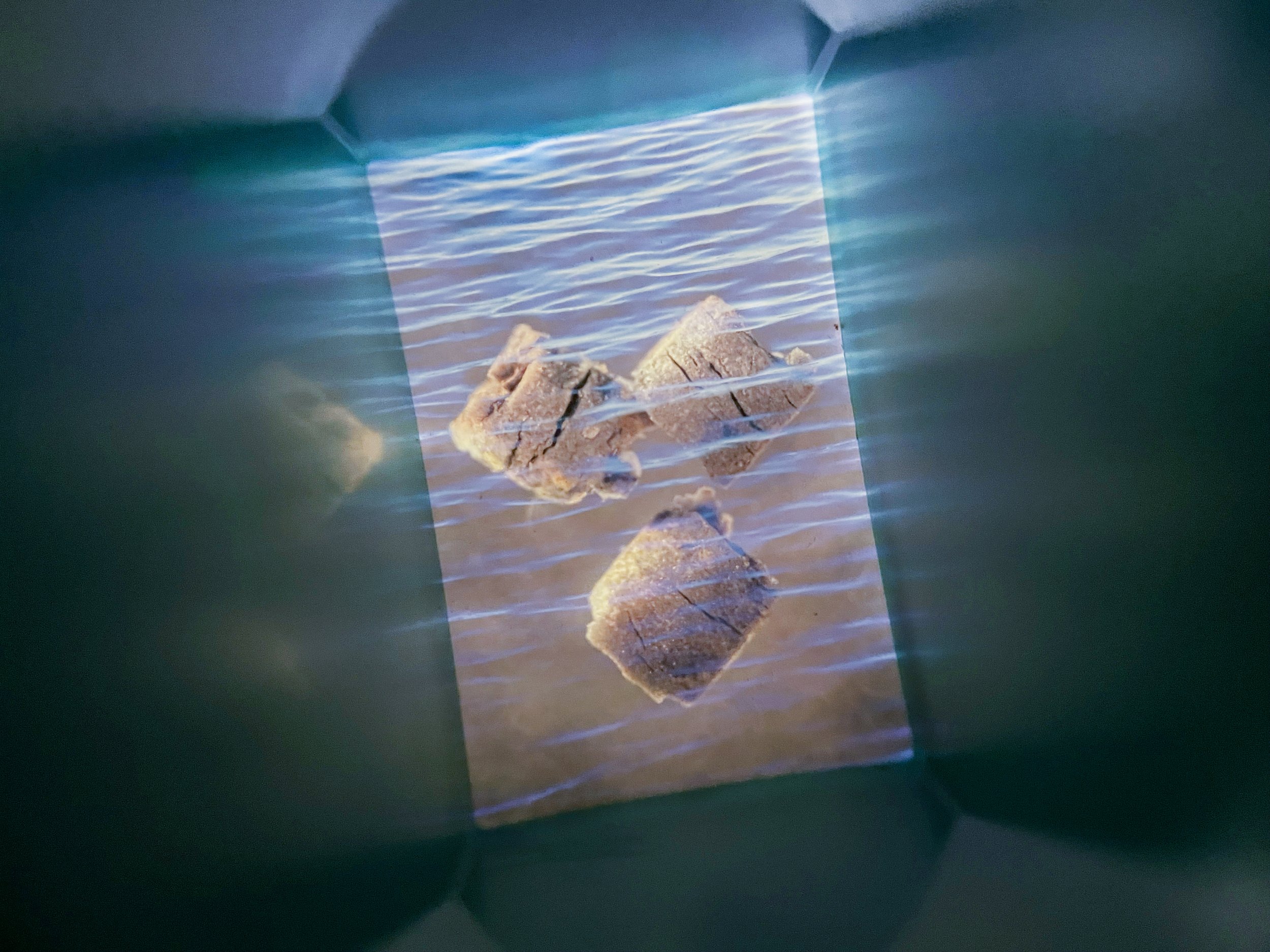

Peep: Human Nature–Micro-viewers, 2024, are a collection of 18 key chain slide viewers. On the first shelf, there are images of nurdles (raw plastic and rubber pellets used in manufacturing), micro- plastics and common plants native to the Lake Champlain watershed. The viewers on the second shelf contain small specimens of a variety of plastics, foam, and shells of introduced species such as the zebra mussel.

Plastic Romance Series (Landscape with Gray Bags and Red Waters)

Plastic Romance Series (Black Grind with Red Water)

Plastic Romance Series (Warning)

Plastic Romance Series (Scape with Seaweed)

Plastic Romance Series (Seascape with Zebra Mussels)

Plastic Romance Series (Landscape with Clam Shell and Nurdle Pearl)

Suspension Series (Nightie)

Edge of Life Vest (Over Troubled Waters)

Edge of Life Vest (Over Troubled Waters)

Edge of Life Vest (Over Troubled Waters); close detail

Porcelain - Limnal Shoe with Algae

Cloacina in Triplicate (Sphaerotilus)

Warhol WaterNet (genus Hyrdodictyon)

Human Nature - Micro-viewers 2024, Rubber Nurdles

Human Nature - Micro-viewers 2024, Clams

Artist Statement

The world is in constant flux, whether viewed on a minute scale or through the lens of the macrocosm, over geologic time or the passing of the sands of an hourglass. Change accumulates, adapts, mutates in the nursery of decay and the unraveling of systems, promoting an opportunity for rearranging and rebuilding that sometimes, gives rise to something new. This process can be fast and violent, or imperceptibly slow; generative or catastrophic depending on what stakes you hold.

Transmutation is the act of transforming, converting or changing one nature into another. It is often associated with alchemy (lead into gold), but it was also an early expression for the process of the evolution of species. As mycologist Merlin Sheldrake notes “all life-forms are in fact processes not things.”

All living things are chemists, bioelectrical engineers, manufacturers, and fabricators. The snail synthesizes a shell by metabolizing raw materials from its environment. Ancient cyanobacteria created a breathable atmosphere releasing oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis. Good for us! But the introduction of oxygen into an anaerobic environment around 2.5 billion years ago set off the first great extinction event killing off numerous species of bacteria that couldn’t metabolize oxygen.

Ancestors of these anaerobes (the bacteria) still exist in low oxygen environments like the bottom of the oceans but are no longer a dominant life form. Humans likewise take resources from the environment and modify them creating new products and waste streams, some of which are beneficial and others disastrous. The difference is that humans can understand the consequences of their actions.

In a very real way, we are living in an era of transmutation because the world around us is changing so fast, giving rise to pandemics and other challenges associated with habitat disruption, loss of biodiversity, pollution and climate change. On the scale of a human life, we are ourselves constantly changing, consuming, and consumed by time. Our physical appearance can alter dramatically while our mental development and emotional states fluctuate, constantly adjusting to or reflecting our different states of being and shifts in our immediate environment. This series of projects reflects observations and ruminations about change—environmental and personal—and how the two are inexorably bound.

An Interview with The Artists

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Sara Schaff: How did this project for Plattsburgh State Art Museum come together?

Robin Lasser: Marguerite and I have worked together, for I don't know, thirteen years, on and off. During the pandemic had a show together at Oklahoma State University, which was called The State We’re In Water. In some ways, the two projects, in Oklahoma and in New York have some overlaps.

Marguerite Perret: And we already knew [Plattsburgh State Museum Director] Tonya Cribb from another project. Our world is small.

Robin: Yeah. Tonya invited us to come to Plattsburgh to do a residency for, you know, seven to ten days, to get to know the community. During the residency we began to initiate some of the collaborations that came to fruition at the exhibit. We met a bevy of scientists from the region, and that extended that to across the lake to meeting the executive director of the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, Chris Sabick, who has a specialized interest in shipwrecks.

Sara: I didn't even know there was a maritime museum.

Marguerite: Oh, yeah, it's amazing.

Robin: It's fantastic. And we got to meet artist David Fadden, and we went to the Six Nations Iroquois Cultural Center where his brother, his father, and I believe his grandfather all had work, and they also shared stories about water.

Marguerite: We also worked with some of the scientists who are associated with the Lake Champlain Research Institute. In particular Aude Lochet. She’s the outreach specialist, and she also teaches in the environmental sciences program [at SUNY Plattsburgh]. Also Tim Mihuc, the director of the institute. They were studying plastics in Lake Champlain, particularly microplastics, which are having such an impact on the environment. Tim talked a lot about species that have been introduced into Lake Champlain and the impact they are having on native species. Like zebra mussels. In Kansas where I teach, all the lakes are full of zebra mussels, and it’s a terrible problem.

Aude invited us to a beach cleanup, and a lot of the work that I present in this show is based on that cleanup, and some of it's cast in porcelain. Some of it is photographed and presented in such a way that it initially looks like something beautiful. But then you have to think about what you're actually looking at.

Sara: I'm fascinated by the porcelain work.

Marguerite: Everything that's in the porcelain pieces, it’s all anthropogenic. It's all some kind of trash or something that was left behind, or it's, you know some paper towels that were dipped in porcelain, or some of it that looks organic. It all has to do with commerce, and the porcelain itself always has this sense of being special and like, you know, “Oh, this is porcelain!”

During the residency, Robin and I had the wonderful opportunity of going to all these places together, and I think having a friend who is also an artistic collaborator with you as you're experiencing all this, and then, later on, going over dinner talking about it, I felt that was also part of the collaboration and the inspiration in both of our work.

Robin focused her response more on social justice and stories of the history of the region, as well as on the impacts of climate change through these amazing immersive videos…or more than videos—films. They're films because they're so beautiful.

Robin: I think of them as melting paintings.

Sara: It’s dreamy to have the kind of artistic collaborative relationship you two have. You can see your conversation in the exhibit. There’s a thematic connection, and then there's a textural and color connection between the pieces, too.

Robin: Thank you for noticing that. I think if I was looking in the room, I wouldn't necessarily know it was two artists contributing, and I kind of love that because quite honestly, that’s how we work. You know, we have our conversations, but in this particular project, before the work went up, we hadn't seen that much of what the other person had produced. We knew, generally speaking, what each other was doing. So yeah, when I walked into the room, and I thought, wow—exactly what you said.

Credit: Marguerite Perret

Credit: Marguerite Perret

Credit: Marguerite Perret

Credit: Robin Lasser

Credit: Robin Lasser

Credit: Robin Lasser

Credit: Robin Lasser

Credit: Robin Lasser

Robin: Marguerite, I feel like your work is often very dense and layered, with, you know text and imagery, with a beautiful sculptural element. I think of your work as a stage.

We share the medium of photography. But I work with in a sculptural way backwards, because almost always I am creating work to be photographed, and then it's often photographed in situ which might be at the lake, or it might be on in my backyard on a barbecue resembling a watershed that's made itself.

So we share sculptural interests, and we also both share a deep commitment to research. I always count on Marguerite for some of the science.

I wasn't sure what approach I would take, because I didn't want to repeat the approach I took in Oklahoma and with our other works. I believe it was Marguerite that said, “You know, there are shipwrecks at the bottom of Lake Champlain,” and we both went—boom!

They’ve existed at the bottom of the lake from the Industrial Revolution to the present. And it's really interesting to both of us, because this demarcates the time where humans have had such a marked change on the weather and the environment. So the bottom of the lake becomes like a librarian's archive of that shift.

Marguerite and I have often worked with climate change in relationship to water and or health. We also have worked on other projects. But climate change is always there.

About six years ago I started, in a very small way, casting ships of ice. But I wasn't pigmenting them yet, and they weren't creating their own watersheds. I think most of us think of melting glaciers as some kind of metaphor, or certainly they’re the most visible barometer of climate change, and I thought, you know, we're gonna go from the macro to the micro in my case with these ships. Having them melt, to me, was sorrow—the weeping, the loss, the memorializing of our history and our and our current state of being.

I photograph them as they're melting. The films are really like moving still images, for the most part, because I'm a photographer at heart. And then I let them dry. I went out the next day, and I noticed things, and I thought, wow, they're drying and cracking in the shape of a river or a lake. And then I would use that same platform, create more ships, melt them, and record as the ship weeps and shape-shifts from barge to waterway or land way.

It not only creates its own watershed, but many of the students and people who came to the show kept referring to my particular pieces on the wall as paintings. And I quickly said, “No, no, they're not paintings.” But then I began to think, oh, yes, they are paintings. I just didn't paint them.

I'm always interested in how things connect. And I wanted to think about how I might connect environmental issues and climate change with social and environmental justice. With David Fadden’s input, I was able to bring in the element of environmental racism. He talked about growing up along a different river than the lake, and the things he experienced along that river. In one of the films, his is one of the voices you hear.

I have to thank Tonya, who initially introduced me to Jacqueline Madison, the president of the North Country Underground Railroad Museum, during the residency. I was very interested in how she talked about Lake Champlain as a gateway to freedom. Waterways as the sort of glory of migration. She said to me, “Robin, everything migrates, everything moves.”

Marguerite: What really interests me is this idea of change and how changes can be very quick. It could be slow. It can be disruptive. And right now we're in a very disruptive, quick-change era.

And so my works that are on display—all of them have an artificiality about them, even though they seem naturalistic. It's as if we are replacing nature with human detritus. People will get maybe drawn to the work because it does look beautiful. But then it's not what you think it is, and you have to kind of parse that out.

I think a lot about different geological eras and how they have been defined. Supposedly we're in the Anthropocene—a lot of people use that term, though it's never really been accepted by most scientists, because it's hard to accept it while it's still happening.

The environment is changing. We're changing. Political views are changing. So what's the best way to adapt? And obviously the best way to adapt, whether you're talking about social justice or more scientific view of environment, is to recognize that we're all part of the system. We're all part of the larger whole.

And when you start disrupting that larger whole, you are also disrupting your own ability to persist and to thrive.

Robin: Can I ask you a question about what you said with that adaption? What do you feel that takes? I was just at the Hammer Museum yesterday, and this artist did a piece and she had all these architectural elements floating like our floating world. And why are they floating? Well, it turns out that most, if not all, of South Vietnam, in 25 years will be greatly affected by flooding if not completely inundated. And we're going to have 20 million people migrating.

Marguerite: I don't know if you can adapt to every situation. I made these two large prints, and I'm thinking that that's going to be a whole series about you know, being in suspension, remnants of human culture. I mean, I don't know if you can adapt to every situation.

Washed up Lady of the Lake (Marguerite Perret)

Wastewater viewers with image inside (Marguerite Perret)

Undulating Wings of Water, detail (Lasser & Perret)

Robin giving a lecture in Burke Gallery

Sara: The exhibition has been a highlight of the campus this semester. It's brought all these different areas of what we do together—including a production of The Water Station [by Ōta Shōgo], directed by theater professor Julia Devine, that incorporated your gorgeous images into the play.

Robin: I feel like Sara—because this is the way my brain works—I feel like what you and your students are doing [with Saranac Review] is a third collaboration.

Sara: I like that.

Robin: And you have such amazing students there.

This show is such a gift to those of us like Marguerite and myself, who work with community engagement as a primary thrust of our investigations. So to see it truly activate the community and the community's own creative process. It's like, it's like parallel play. Let's all play together. Let's all create together.

Robin Lasser is a Professor of Art at San Jose State University produces photographs, video, site-specific installations, and public art dealing with public health, environmental issues, and social justice. Lasser often works in a collaborative mode with other artists, writers, students, public agencies, community organizations and international coalitions to produce public art and promote public dialogue.

Lasser exhibits her work nationally and internationally, including the SF Asian Art Museum, San Jose Museum of Art, National Gallery of Modern Art Bangalore India, the Museum of Goa India, Exploratorium Observation Gallery in San Francisco, Kohler Museum of Art, The Metenkov Museum of Photography, Yekaterinburg, Russia, the Recoleta Cultural Center in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and the Caixa Cultural Center in Rio De Janeiro. She also participates in international biennials such as ZERO1: Global Art on the Edge, San Jose, California, Nuit Blanche, Toronto, Canada and the Pingyao International Photography Festival in Pingyao, China.

Marguerite Perret is an Associate Professor of Art at Washburn University. Her arts-based research and social issue-engaged studio practice explores the promise, complications and sometimes contradictory narratives inherent at the interstices of art, science, healthcare and personal experience. She is the lead artist for the international and interdisciplinary dialogue “The Waiting Room Projects,” and has presented her collaborative work nationally and internationally. Recent commissions, temporary public art projects, collaborative installations, exhibitions and artist residencies include those at the Oklahoma State University Museum of Art, Stillwater, the University Museum, Groningen, the Netherlands, the International ZERO Biennial in San Jose, California, the Loyola University Museum of Art, Chicago, Montalvo Art Center, Saratoga, California and the Anderson Center for Interdisciplinary Arts, Red Wing, Minnesota. Publications include A Waiting Room of One’s Own: Contexts for the Waiting Room (2011), and “things you should know about”/Speak Loudly booklet series (2013 and ongoing).